Executive Summary

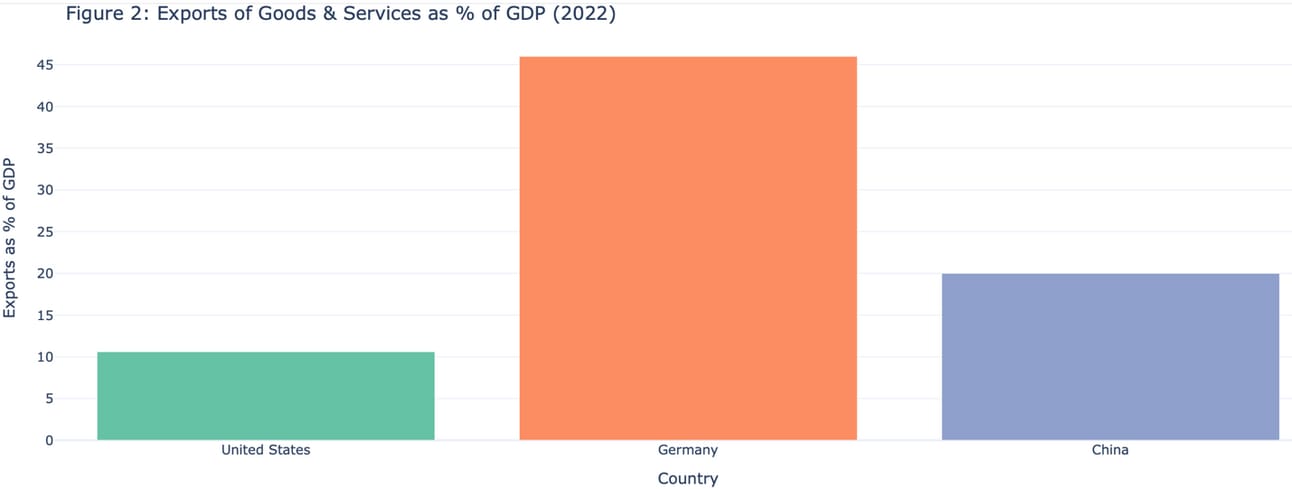

Despite historical dominance in global exports, today U.S. exports contribute approximately 10% to its GDP, considerably lower than export-driven nations such as Germany (45%) and China (20%). Instead, America's economic prowess largely stems from the global operations of its multinational corporations, whose foreign affiliates generate around $6.5 trillion annually, overshadowing direct exports totaling approximately $2.5 trillion. Manufacturing for export faces substantial challenges, including high labor costs, significant skills gaps, and complicated international non-tariff barriers (NTBs—regulatory measures countries use other than tariffs to control imported goods).

To effectively respond, the U.S. must prioritize fair reciprocity in trade policies, dismantle NTBs, actively support small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs—businesses defined by limited employee count and revenue thresholds), and invest substantially in workforce training programs. Additional emerging considerations such as supply chain resilience and securing critical minerals must also be central in shaping a forward-looking 2025 trade strategy.

Historical U.S. Export Dominance in the Industrial Era

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the United States emerged as a global export powerhouse. American agriculture fed the world: in 1898, U.S. wheat and flour exports reached about 224 million bushels. By 1900, farm goods made up 62% of all U.S. exports, underscoring how dominant U.S. commodities were on world markets. The United Kingdom was the top buyer of American grain at the turn of the century, and U.S. wheat exports regularly exceeded 100 million bushels per year in that era. Beyond food, American manufactured goods also spread worldwide. American consumer brands were household names abroad even before WWII – by the late 1800s, companies like Ford (autos), Heinz (foods), Colgate (toiletries), and Gillette (razors) were selling in Europe and especially Britain. In the early 1900s, popular U.S. products from Singer sewing machines to Kodak cameras could be found on shelves and in households from London and Tokyo, reflecting America’s industrial might and global marketing reach. In short, well before mid-century, the U.S. was both the world’s largest economy and a leading exporter across agriculture and consumer goods.

This export dominance persisted into the mid-20th century. The U.S. was often termed the “world’s breadbasket” for its grain exports. Even as other nations industrialized, America remained a top exporter of key commodities: for example, by 1970 the U.S. supplied ~50% of global corn exports and ~33% of wheat exports. U.S. industrial exports also flooded foreign markets, aided by post-WWII reconstruction demand. American wheat, cotton, machinery, and automobiles became staples of international trade. By the late 20th century, the U.S. was exporting one-third of all globally traded wheat and 70% of traded corn, an unrivaled market share. This historical record shows that exports have long been a part of the U.S. economic story – but as the next sections detail, the relative importance of exports to the American economy has declined, even as U.S. companies remain deeply engaged internationally.

Graph 1: US Agricultural Export Dominance (1900-1910). The U.S. share of Wheat World Exports hovered during the 20th Century’s First Decade around 50%.

Multinationals Over Exports: America’s Post‑War Trade-Off.

Why has the United States historically been relaxed about export growth and trade imbalances? In large part, it’s because America found another way to win globally – through the dominance of its multinational corporations. In the decades since WWII, U.S. leaders often downplayed the importance of expanding exports for its own sake. Instead, they encouraged U.S. businesses to expand overseas, confident that American firms could reap the benefits of foreign markets one way or another. The result was a grand trade-off: America opened its vast home market to imports – even to the point of huge trade deficits – and in return, U.S. companies quietly entrenched themselves around the world and earned billions.

By the 1960s, it was clear that the U.S. economy was far less export-dependent than its peers. Blessed with a huge domestic consumer base, the U.S. consistently had exports make up under 5% of its GDP in the post-war decades. Washington could thus afford a more relaxed trade stance. As long as the overall economy thrived on internal demand, policymakers were not overly alarmed that, say, West Germany or Japan were exporting more than the United States. In fact, U.S. strategists saw benefits in allowing allies to run trade surpluses: it fueled their recovery and bound them closer in the fight against communism. American trade policy after WWII was less about mercantilist export gains and more about building a liberal, U.S.-led order.

Officials tolerated partners’ protective policies and “turned a blind eye” when reciprocity in trade wasn’t met. The implicit logic was simple: let other countries boost their exports – the United States will still come out on top in the end.

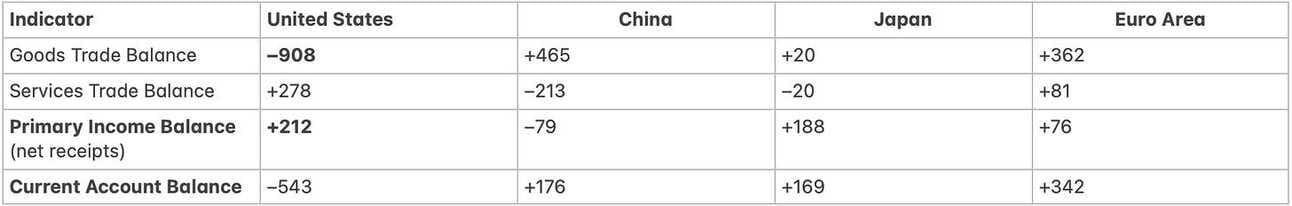

Table 1: U.S. Trade Balance vs. Overseas Income (Avg. 2017–2021, in billions USD)

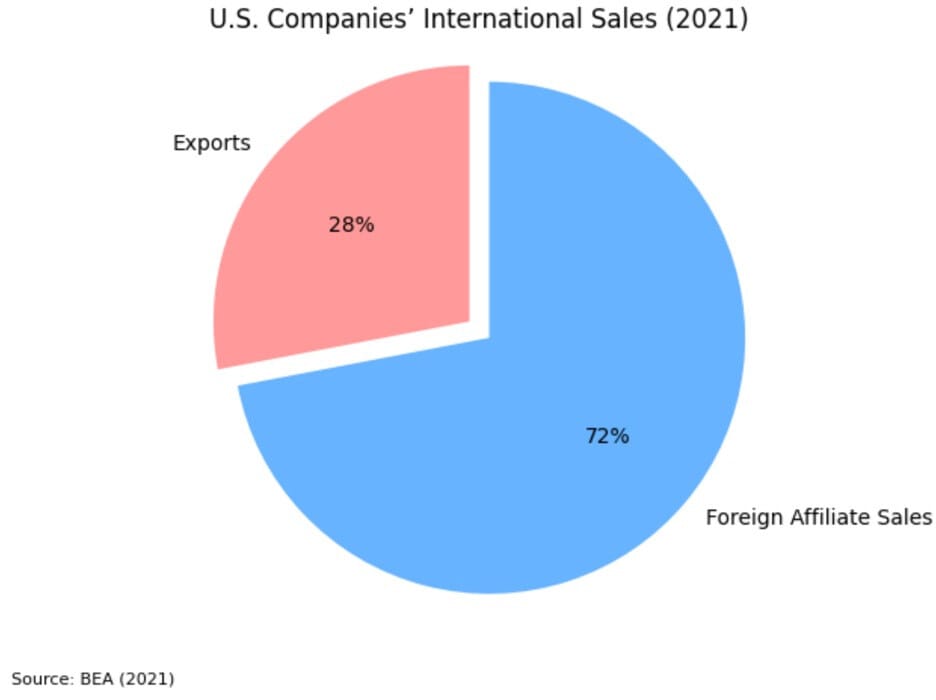

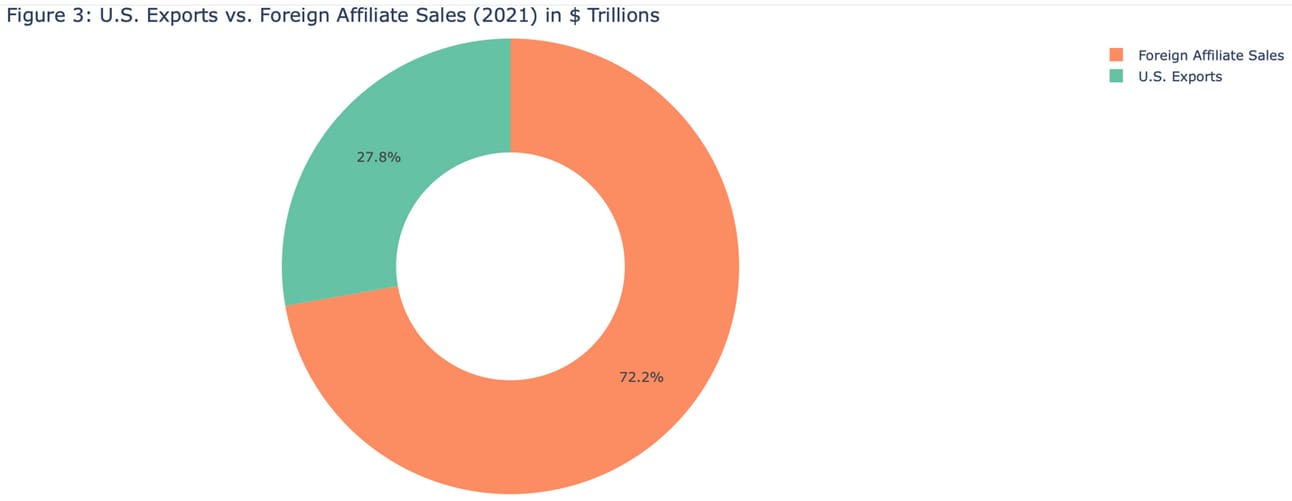

By 2021, sales by foreign affiliates of U.S. multinationals had reached $6.5 trillion, significantly overshadowing direct exports valued at $2.5 trillion. Companies such as Ford and Coca-Cola established extensive operations overseas, bypassing tariffs through local production. This strategy, though economically advantageous internationally, triggered profound domestic impacts, including significant manufacturing job losses and economic dislocation, particularly within industrial hubs such as the Rust Belt.

Figure 1: How U.S. Companies Deliver Goods/Services to Foreign Customers (2021, BEA). Only 28% via direct exports; 72% from U.S.-owned foreign affiliates.

How exactly did the U.S. “come out on top”? By leveraging the unrivaled reach of its multinational corporations. Rather than fighting every foreign tariff with reprisals, the U.S. often let its corporations do the work of penetrating foreign markets. American companies built factories in Europe, bought mines in Latin America, and set up subsidiaries across Asia and Africa. This meant that even if a car wasn’t “Made in Detroit” and exported, an American automaker (say, Ford) might still sell it in London via its British subsidiary – and earn the profit. Over time, the revenues U.S. companies generated through their foreign affiliates dwarfed the value of U.S. exports. For example, by 2007, U.S. firms’ majority-owned foreign affiliates were selling ~$4.7 trillion worth of goods and services abroad annually– over four times the value of U.S. exports of goods that year. These affiliates aren’t primarily shipping things back to America; well over 80% of their sales stay overseas, satisfying foreign demand on foreign turf. The crucial point: **U.S. corporations found they could earn global profits without needing to export from the U.S. (and without being as vulnerable to foreign import barriers).

Consider a concrete example: the Apple iPhone. The U.S. runs a trade deficit with China in electronics partly because iPhones (assembled in China) count as imports. But who gets the profit? Not primarily the Chinese factory – it’s Apple Inc. Apple is an American company, and it captures the bulk of the iPhone’s value. The design, software, and marketing are done in California. When an iPhone is sold in Europe or Asia, that’s revenue in Apple’s coffers, even if it never passed through U.S. export stats. This pattern repeats across industries. Boeing jets flying over Dubai, Coca-Cola bottling plants in Africa, Hollywood films in a Sydney theater – all generate income for America’s corporate sector overseas, even if no “export” from the U.S. is recorded.

Because of these massive overseas operations, the United States earns a huge amount of investment income from the world. Every year, U.S. companies repatriate profits, and U.S. investors receive dividends and interest from abroad, to the tune of hundreds of billions of dollars. In fact, in recent years those net receipts from abroad have regularly exceeded $200 billion per year. This helps offset the trade deficit. It’s not a coincidence that the U.S. can run persistent trade deficits and yet not suffer a financial crisis – the rest of the world is effectively paying rent to Team America, Inc. As one policy analysis observed, America’s net earnings from abroad are impressively large, even though foreigners own more U.S. assets than Americans own foreign assets. Why? Because U.S. assets – often in the form of those powerful multinationals – yield higher returns. In plain terms, an American dollar invested in China or Europe tends to earn more than a foreign yuan or euro invested in the United States. The U.S. has been astute (or lucky) in this regard – it built the brands, technology, and networks that generate robust profits globally.

There’s also a cost advantage that the U.S. has enjoyed by “importing” so much: cheaper goods and inputs for American consumers and industries. By integrating into global supply chains, the U.S. gained access to raw materials and manufactured products at lower prices than if it tried to produce everything domestically. American agribusiness gets fertilizers and machinery from all corners of the world; U.S. electronics firms source components from Asia where production is cost-efficient. A recent Cato Institute report put it succinctly: access to globally priced imports is a boon – it makes American companies more competitive and American consumers better off with lower prices. So in a very real sense, the U.S. trade deficits have been buying something of great value: low inflation and high corporate profits. Other countries, from Germany to China, essentially helped subsidize the American standard of living by selling goods cheaply, while U.S. firms often led, orchestrated, or financed those global production networks.

None of this is to say that trade imbalances are without downsides – clearly, many U.S. manufacturing jobs were lost and some communities suffered from factory offshoring. But from the vantage of U.S. economic strategy, one can see why administration after administration didn’t panic about rising imports. The broader U.S. economy was still benefiting in aggregate: either via U.S. companies dominating overseas or via consumers enjoying affordable imports (and often, both at the same time). It’s a complex, somewhat paradoxical picture: America “the deficit runner” nonetheless remained America the global profit center. As long as the dollar stayed dominant and foreign capital flowed into U.S. assets, this system was sustainable. The U.S. could allow trading partners to be mercantilist – exporting far more than they imported – and yet the U.S. would reap many rewards of that very imbalance (cheap goods, high asset prices, foreign earnings, etc.).

In sum, since WWII the United States has arguably pursued a grand bargain: tolerate a degree of unequal trade (structural imbalances and even foreign protectionism) in exchange for the unparalleled global reach of U.S. corporations. Washington’s bet was that what’s good for Ford or IBM abroad will ultimately be good for America – even if Ford is making cars in Europe or IBM is servicing clients in Asia. For decades, that bet paid off in the form of American economic primacy, albeit with painful adjustments for certain sectors. Now, as global dynamics shift and rivals emerge, this approach is being debated anew. But historically, it’s clear that exporting democracy often went hand-in-hand with exporting Corporate America – and that strategy helped the United States remain the world’s economic hegemon without needing an export-led economy at home.

Exports as a Share of GDP: U.S. vs. Export-Driven Economies

Despite its past export prowess, in recent decades exports have become a surprisingly small fraction of U.S. economic output. The United States today is far less export-dependent than many other major economies. In the last 5–20 years, U.S. exports of goods and services have typically accounted for only about 10% (or less) of U.S. GDP. For example, in 2023 exports were ~11% of GDP, and they have hovered in the high single digits to low teens percentage-wise for much of the 2010s and 2020s. This indicates that roughly 90% of American economic activity is driven by domestic consumption and investment, not by sending products abroad.

By contrast, export dependence in countries like Germany and China is dramatically higher. Germany’s economy is heavily geared toward foreign markets – exports equal roughly 45–50% of German GDP in recent years. (In some years earlier, it exceeded 50%, though it has moderated slightly to the mid-40s percent range.) China also relies on exports more than the U.S., although to a lesser extent than Germany. Exports of goods and services make up about 20% of China’s GDP as of the early 2020s, down from higher levels in the 2000s but still double the U.S. share. Figure 1 illustrates this stark gap – the U.S. around ~10% vs. export-driven nations at 20–50% of GDP.

Figure 2: Exports of Goods & Services as a percentage of GDP. The U.S. economy (gray) relies on exports for only ~10% of GDP, whereas Germany (red) is about 45–50% and China (blue) ~20%, based on recent data.

Several factors explain this difference. The U.S. has a huge internal market, so American firms can achieve scale domestically without always needing to export. In addition, U.S. companies often reach global customers through means other than U.S.-sourced exports – a point we explore below – such as local subsidiaries in foreign countries. Meanwhile, Germany’s economy is specialized in tradable industrial goods (cars, machinery, chemicals) with a smaller domestic market, forcing German firms to be export-oriented. China, as the “world’s factory,” still depends on exporting mass-manufactured products, although rising domestic consumption has reduced the export share of China’s GDP to around 20%. Smaller advanced countries (e.g. South Korea) often have even higher export/GDP ratios.

The key takeaway is that the United States is a relatively closed economy in GDP terms, with exports typically in the 8–12% of GDP range. This is orders of magnitude lower than export-centric economies that range from 20% up to 50%+. Consequently, the U.S. is less vulnerable to export downturns but also less directly driven by export growth. Yet, as we’ll see, this doesn’t mean American business isn’t global – rather, it means much of its global engagement happens through other channels.

American Companies’ Global Presence and Operations

One reason exports are a smaller share of U.S. GDP is that American companies have long operated abroad directly, generating revenue in foreign markets through their overseas subsidiaries, joint ventures, and foreign employees. The U.S. economy “goes global” largely via these multinational enterprises. Many of the largest U.S. firms earn the majority of their revenue outside the United States, maintain extensive foreign operations, and have been present internationally for decades. Table 1 highlights a mix of legacy and new-era companies to illustrate the scale of U.S. business presence abroad:

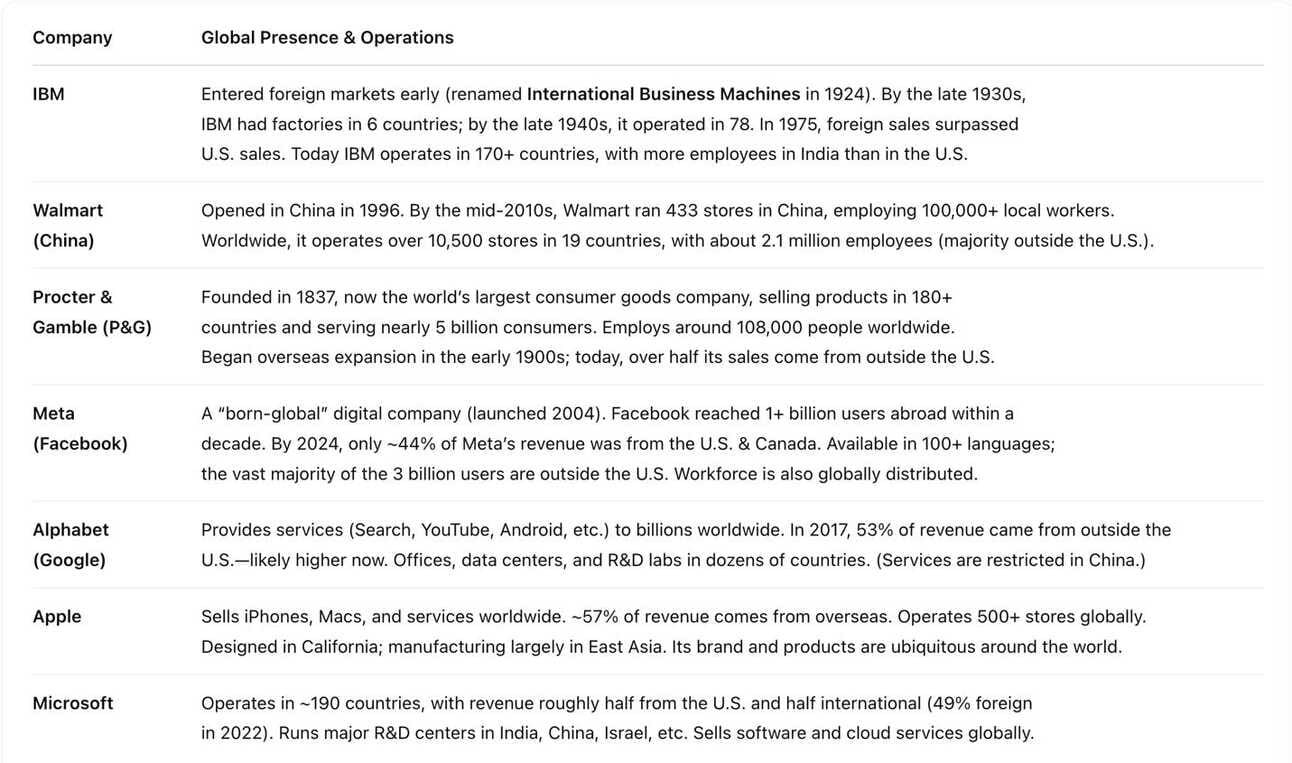

Table 2: Examples of U.S. companies’ long-standing international presence, with key metrics on foreign operations.

Each of these firms has deep in-country operations abroad, from local hires to local production, which often substitutes for exporting from the U.S. For instance, when Walmart builds stores in China and hires 100k local staff, the sales generated count as part of China’s retail activity (not U.S. exports) – yet the profits accrue to a U.S. company, and often U.S. headquarters supplies management expertise, IT systems, etc. Similarly, IBM’s decision to “arrive early” and invest directly in markets like Brazil (starting in 1917) and Europe made it one of the first truly multinational corporations. By engaging via foreign affiliates, IBM and others effectively deliver American business output globally without it showing up as U.S. export statistics.

The aggregate impact of this strategy is massive. Sales by foreign affiliates of U.S. multinationals are far larger than U.S. exports. In 2021, majority-owned foreign affiliates of U.S. companies had combined sales of about $6.5 trillion worldwide, compared to total U.S. exports of about $2.5 trillion. In other words, U.S. firms sold nearly three times more through their foreign subsidiaries than through exporting from America’s shores. Figure 2 illustrates this breakdown: only ~28% of U.S. companies’ international sales come from exports, while ~72% are generated by their in-country foreign operations.

Figure 3: How U.S. companies deliver goods/services to foreign customers (2021). Only 28% was via direct exports from the U.S., whereas 72% came from sales by U.S.-owned foreign affiliates.

This pattern has been called the “best kept secret” about U.S. global commerce– that investment and local presence, rather than cross-border trade, drive American companies’ engagement abroad. It explains how the U.S. economy can be less export-dependent (as a share of GDP) even while American firms are extremely globalized. Instead of simply shipping goods from, say, Ohio to Germany, a U.S. manufacturer might build a factory in Germany and sell directly within Europe. The revenue earned still ultimately benefits the U.S. firm (and often U.S. shareholders), but it doesn’t count as an export. This model of globalization – “produce there to sell there” – has long been a hallmark of U.S. multinationals, and it’s a key reason the U.S. trade balance alone doesn’t capture the full picture of U.S. economic interests overseas.

How the U.S. Earns Revenue Abroad: Sectoral Breakdown

The United States is often described as a post-industrial, service-oriented economy, and this is reflected in the composition of its international earnings. When looking at what the U.S. sells to the world (whether via exports or affiliate sales), services and intangible assets loom large alongside physical goods. Below is a breakdown of major channels of U.S. revenue generation abroad:

Services Exports: The U.S. is the world’s #1 exporter of services – including financial services (banking, insurance), professional and technical services (consulting, engineering, legal, R&D), education and travel (foreign students and tourists spending in the U.S.), royalties and license fees (use of intellectual property), and digital services. In 2022, U.S. exports of services totaled $926 billion (in areas like finance, tech, IP, etc.), which was about 30.7% of all U.S. exports. This share has been rising as America’s comparative advantage often lies in high-value services. For instance, U.S. firms lead in intellectual property (IP) royalties – licensing music, software, patents, trademarks and franchises abroad generated nearly $130 billion in IP export revenue in 2022, more than any other country (Germany was a distant second at ~$53B). Iconic examples include Hollywood films and U.S. streaming content earning royalties globally, Microsoft and Oracle collecting software licensing fees worldwide, or franchisors like McDonald’s and Hilton hotels earning franchise royalties from thousands of overseas outlets. The knowledge economy is a major U.S. export: American innovations, entertainment, and brands are monetized internationally through service contracts and licenses.

Goods Exports: The U.S. still exports a huge volume of physical goods – around $1.8–$2.0 trillion worth of goods annually in recent years. Top U.S. merchandise exports include aircraft and aerospace equipment, automobiles and auto parts, semiconductors and electronics, industrial machinery, pharmaceuticals, petroleum and chemicals, and agricultural products (like soybeans, corn, and meat). In 2022, the largest categories were industrial supplies (e.g. chemicals, oil) at 38% of goods exports, capital goods (machines, tech equipment) at 29%, with consumer goods (14%) and autos (8%) also significant. However, relative to the size of the U.S. economy, these exports are modest (as discussed, ~10% of GDP). Moreover, many U.S. manufacturers derive more international revenue from factories they’ve established abroad. For example, a company like Caterpillar might export some heavy machinery from Illinois, but it also builds tractors in Brazil for the Latin American market. Thus, goods exports are just one part of the global earnings mix for U.S. firms. It’s notable that the U.S. consistently runs trade deficits in goods (importing more than it exports) but surpluses in many services, highlighting the shift toward service-based international revenue.

Foreign Affiliate Sales: As shown earlier, the bulk of U.S. overseas business happens through foreign affiliates. These sales span all sectors – from auto assembly plants in Mexico, to Coca-Cola bottling operations in Africa, to Citibank branches in Asia. A considerable portion of these local sales are in services (e.g. an American consulting firm’s overseas office advising a foreign client, or a U.S. fast-food chain’s foreign franchises selling meals) and in manufacturing (vehicles, electronics, consumer goods produced abroad by U.S. firms and sold locally). Importantly, services delivered via affiliates (like a U.S. law firm’s overseas practice) do not show up as U.S. exports but still generate income for the U.S. company. According to the U.S. International Trade Commission, in sectors like finance and tech, foreign affiliate sales often exceed cross-border export sales. This means the U.S. “exports” a lot of services by having a presence on the ground in foreign markets (sometimes termed Mode 3 trade in services).

Digital Platforms and Data: In the 21st century, U.S. technology platforms have become major channels of international value, albeit harder to quantify in trade stats. Companies like Google, Facebook, Amazon, Microsoft, and Apple deliver digital services to billions of foreign users. The revenue model is often advertising (for Google/Meta) or app sales and subscriptions (Apple’s App Store, Microsoft’s cloud services). These earnings largely count as service exports or overseas affiliate revenue. For example, advertising sold by U.S. tech firms to businesses in Europe or Asia is effectively an export of advertising services. Meta’s advertising income from an Indonesian user is recorded as revenue in the U.S. (if the sale is billed through a U.S. entity), contributing to the service export surplus. However, tech companies may also route revenues through foreign subsidiaries for tax purposes, muddying the categorization. Nonetheless, it is clear that U.S. digital services (social media, search, streaming, software) are a dominant force globally, and this represents a modern form of export – one measured in bytes and bandwidth. The U.S. runs a significant surplus in digitally deliverable services. Policies that allow free flow of data across borders, and fair access to foreign digital markets, therefore directly impact U.S. economic interests.

In summary, the U.S. earns money internationally through a diverse portfolio of activities: traditional exports of planes and grains, a booming trade in services and IP, franchise and royalty networks, and the on-the-ground sales of its multinationals, including via digital platforms. This multi-pronged approach has some advantages – it’s resilient (service exports are steadier than goods), it leverages U.S. strengths in innovation and brand value, and it circumvents many trade barriers (you can’t “tariff” a local subsidiary’s sales the way you can tariff an import). However, it also means U.S. jobs at home don’t grow as directly from export expansion, since the foreign affiliate model can offshore production. It’s a double-edged sword: great for U.S. corporate profits and global reach, but part of the reason domestic manufacturing employment has not kept pace.

Why Manufacturing for Export Is Increasingly Challenging in the U.S.

While the U.S. still manufactures a lot (it’s consistently in the top two manufacturing nations by value), certain types of export-oriented manufacturing have shifted abroad. There are structural reasons why many products Americans consume (or companies design) end up being made overseas. Key factors include higher labor costs, skill gaps in the workforce, and the development of robust supply chain ecosystems in other countries – all of which make manufacturing in the U.S. for export relatively less competitive.

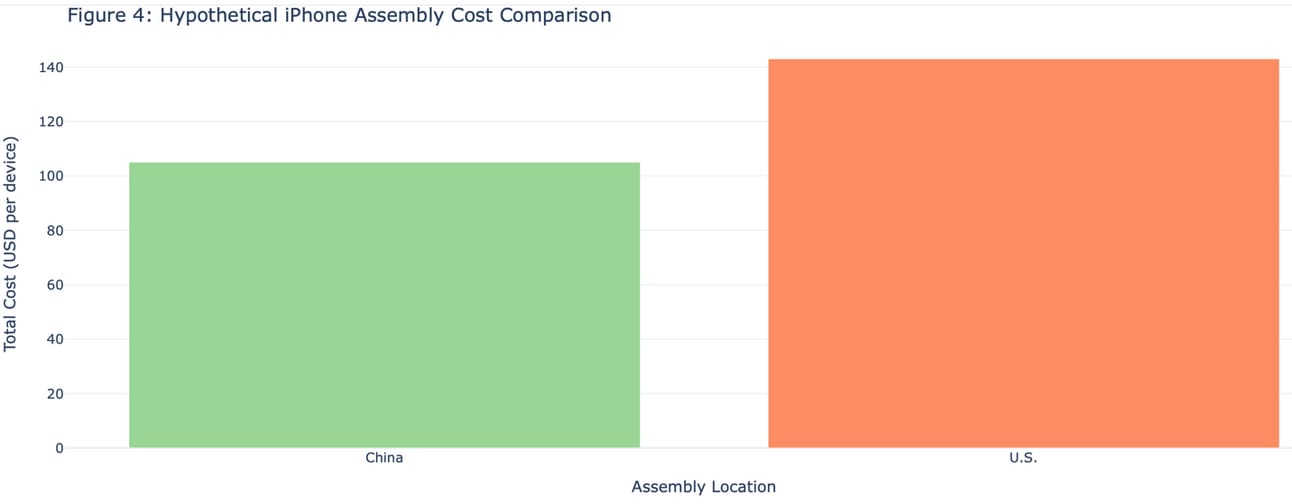

Labor Costs: American manufacturing workers are significantly more expensive (in wages and benefits) than workers in emerging economies. This wage gap, especially for labor-intensive assembly work, has been a major driver of offshoring. For example, China, Mexico, Vietnam, and other countries can often produce goods with labor costs that are a fraction of U.S. levels. Even when productivity is higher in the U.S., the cost difference in industries like electronics assembly is hard to overcome. An oft-cited illustration: Apple’s iPhone is designed in California but assembled in China by Foxconn. In the late 2000s, President Obama asked Steve Jobs what it would take to build iPhones in the U.S. – Jobs’ reply was blunt: “Those jobs aren’t coming back.”

He was referring to the tens of thousands of semi-skilled manufacturing jobs Apple had in China. The cost structure (and supply chain) in China simply made it infeasible to bring that work to America at anywhere near the same cost. An analysis by CNNMoney found that labor was a major reason: manufacturing an iPhone in the U.S. would add tens of dollars in labor cost per unit, which at Apple’s scale was prohibitive. For commoditized products with thin margins, even a small cost penalty can push production abroad.

Skilled Workforce and Scale: It’s not just cheaper workers – in some cases the U.S. lacks sufficient numbers of certain skilled manufacturing personnel. The Apple case again is instructive. When Apple was gearing up mass production of the iPhone, it found it needed 8,700 industrial engineers to oversee the assembly line and tens of thousands of specialized technicians. In China, Apple could find and hire that many engineers literally within weeks. In the United States, it was estimated it would take 9 months to assemble a comparable engineering workforce. The flexibility and sheer scale of the labor pool in places like China (and the existence of entire “factory cities” devoted to electronics) give those countries an edge for big manufacturing projects. American manufacturing employment peaked in the late 1970s; since then, many vocational training pipelines have shrunk. Industries like welding, tool-and-die making, and precision machining report shortages of younger skilled workers as older ones retire. So when a multinational considers where to manufacture a new product, they must consider whether the local workforce can quickly staff up. Often, Asian manufacturing hubs can mobilize huge workforces (including engineers on site) on short notice, which is difficult in the U.S. unless it’s a highly automated factory.

Manufacturing Ecosystems: Over decades, entire supplier ecosystems have developed in certain regions outside the U.S. – for example, the cluster of electronics suppliers in East Asia, or textile and apparel networks in South Asia. These clusters mean that a company building a complex product (like a smartphone or a car) can find most of the needed parts and materials nearby, and can rapidly adjust production by tapping a network of subcontractors. China’s Pearl River Delta is famously able to produce or source every component of a phone within hours. By contrast, if one tried to build the same phone in America, many components would have to be imported anyway, or the supply chain would be far-flung across states, adding time and cost. In addition, foreign governments often offer generous support: China, for instance, has provided subsidies, tax breaks, and infrastructure to support manufacturing, making it even harder for the U.S. to compete on cost. Manufacturing in the U.S. also faces higher costs from regulations (environmental, safety, etc.) which, while providing important protections, do add to expenses that low-cost countries may not bear at the same level.

All these challenges were encapsulated in The New York Times’ investigation into Apple’s supply chain: “It isn’t just that Chinese workers are paid less; it’s that the infrastructure is more modern, the government support is greater, and the workers have better skills,” the report noted. This trifecta makes certain manufacturing tasks are simply more efficient outside the U.S. It’s not universally true for all industries – the U.S. still manufactures sophisticated aircraft, pharmaceuticals, industrial machinery, etc., often for export. But for a wide range of consumer electronics, appliances, apparel, and even many autos, the economics often favor production overseas (for local sale or export back to the U.S.).

Figure 4: Comparative Costs of Manufacturing an iPhone in China vs. The U.S.

Workforce shortages in manufacturing are a growing concern as well. In 2023, U.S. factories had hundreds of thousands of unfilled jobs – a reflection of both a skills mismatch and less interest from young workers in factory careers. Fields like semiconductor fabrication require very specialized skills, and with the recent push to reshore chip manufacturing, companies are scrambling to train technicians. It’s clear that rebuilding certain manufacturing capabilities domestically would take significant time and investment in human capital.

In short, high-value, high-complexity manufacturing can still thrive in the U.S., but labor-intensive assembly-line production has largely moved to lower-cost locales. As Steve Jobs’ comment implied, once an ecosystem (of suppliers, skills, and cost structure) has been established abroad, it’s hard to reverse. This is one reason U.S. exports (which come largely from domestic production) haven’t grown as fast as imports – many companies chose to serve global demand by producing in situ overseas.

As the U.S. strategizes to maintain its economic primacy through innovation, one emerging sector underscores America's historical legacy of pioneering transformative technologies—cryptocurrency and blockchain. Among these innovations, Bitcoin stands prominently, exemplifying a new wave of digital assets reshaping global financial landscapes.

Bitcoin: A Paradigm of American Innovation and Global Adoption

Bitcoin exemplifies American ingenuity, highlighting the nation's historical strength in fostering disruptive innovation with global impact. Created in response to vulnerabilities exposed by the 2008 financial crisis, Bitcoin introduced a revolutionary decentralized financial technology, quickly transcending national borders. This distinctly American innovation resonates globally, providing robust solutions for international commerce, enhancing economic resilience, and facilitating transactions independent of traditional banking systems.

Like iconic American innovations such as Ford automobiles, Apple smartphones, and Coca-Cola beverages, Bitcoin has rapidly achieved global adoption, offering economic empowerment and financial inclusivity to users worldwide. Its decentralized nature mitigates traditional financial barriers, significantly benefiting regions with limited banking infrastructure or economic instability. By providing secure, transparent, and accessible means for international trade and investment, Bitcoin reinforces America’s legacy as a pioneer of technologies that profoundly reshape global markets.

The 2011 Silicon Valley Dinner: Obama’s Question to Apple’s CEO

In February 2011, President Barack Obama met with a group of Silicon Valley tech leaders – a gathering that included Apple CEO Steve Jobs, Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, and Google’s Eric Schmidt, among others. During the dinner, President Obama posed a pointed question to Steve Jobs about U.S. manufacturing. Noting that Apple was employing hundreds of thousands of workers in China to make its devices, Obama asked Jobs “what would it take to make iPhones in the United States?” – essentially, why can’t that work come home. This question reflected broader concerns at the time: Apple’s products, which once proudly bore “Made in America,” were now almost entirely produced overseas. Obama was pressing Jobs on when – if ever – those manufacturing jobs might return to American soil.

Steve Jobs’ Blunt Reply: “Those Jobs Aren’t Coming Back”

Steve Jobs did not sugarcoat his answer. “Those jobs aren’t coming back,” he told the President bluntly. According to one dinner guest’s account (later reported in The New York Times and Walter Isaacson’s biography of Jobs), Jobs’s reply was unambiguous – a stark acknowledgement that Apple’s vast manufacturing operations in Asia could not simply be transplanted to the U.S. This terse exchange highlighted a harsh economic reality: by 2011 Apple had sold tens of millions of iPhones and iPads, almost all assembled in China, and Jobs believed the established Asian supply chain and workforce advantages were essentially insurmountable in the near term. (It’s worth noting that less than two years later, Apple did take a small step to “reshore” a fraction of production – announcing a $100 million plan to build some Mac computers in the U.S. – but even that move was limited and seen by some as largely symbolic .)

Jobs’s Explanation: China’s Workforce Scale vs. U.S. Skills Gaps

Behind Jobs’s famous one-liner was a deeper explanation. He elaborated that China’s industrial workforce had scale and skills that the U.S. could not match at the time. In Isaacson’s biography, Jobs noted that Apple had some 700,000 factory workers in China, and supporting those assembly lines required around 30,000 manufacturing engineers on-site. “You can’t find that many in America to hire,” Jobs said, explaining to Obama that the rapid supply of technically skilled workers in China was a critical advantage. These factory engineers were not Ph.D.-level researchers, but people with “basic engineering skills for manufacturing” – the kind of training one could get at tech schools or community colleges. China’s ecosystem could produce and mobilize this workforce extremely quickly. Jobs gave an example: Apple had estimated it would need about 8,700 industrial engineers to oversee and guide 200,000 assembly-line workers for the iPhone; in the U.S. it might take 9 months to find that many qualified engineers, but in China it took just 15 days. In short, China offered a massive, readily available pool of mid-level engineers and technicians, plus the ability to scale up assembly overnight, that U.S. manufacturing simply couldn’t match at the time.

Jobs also pointed out that Apple wasn’t choosing China simply for low wages – in fact, he admired the “robust ecosystem” of suppliers and skilled labor there. Chinese factories could ramp up production quickly and were co-located with parts suppliers, allowing last-minute design changes and fast execution in a way U.S. facilities couldn’t easily replicate. He did acknowledge labor cost was a factor too, as Chinese assembly workers earned a small fraction of U.S. wages, but the “speed” and flexibility of the Chinese workforce was the decisive factor.) Jobs concluded that. If the U.S. could train enough of these engineers, Apple “could move more manufacturing plants here” – implying that America’s shortage of suitable technical workers was a key obstacle to building iPhones at home.

Fact-Checking Jobs’ Claims on U.S. Engineers and Jobs “Not Coming Back”

Steve Jobs’ stark claims raised the question: Was the U.S. really incapable of supplying 30,000 manufacturing engineers? In 2011, the United States was graduating tens of thousands of new engineers each year – but the figures depend on how you count. In 2009, for example, U.S. universities awarded about 126,000 engineering degrees (bachelor’s, master’s, and Ph.D. combined). At the bachelor’s level alone, roughly 75,000 to 80,000 engineers were graduating per year around 2010. On paper, that total far exceeds the “30,000” gap Jobs cited. However, Jobs’ point was about the specific type of engineers needed and the speed of hiring. Many of those U.S.-trained engineers were pursuing software jobs, research roles, or other sectors; relatively few were the kind of industrial or manufacturing engineers willing to work on factory floors. In fact, contemporaneous reporting backed up Jobs’ concerns: manufacturing executives complained of a “skills gap” – a dearth of Americans with more than a high school diploma but less than a four-year engineering degree, the very technicians and tech-school graduates that factories rely on. “They’re good jobs, but the country doesn’t have enough [people] to feed the demand,”said an MIT official about this shortage in the context of Apple’s supply chain.

It’s also true that not all U.S.-educated engineers were available to private industry. Jobs reportedly argued that a significant chunk of American engineering graduates ended up working for the U.S. government or in defense. (This claim is plausible: a portion of engineers go into government labs, military contracting, infrastructure projects, etc., though quantifying it as “25%” of graduates is difficult to verify without specific data. It does underscore that Apple and other tech firms were competing with government agencies and defense contractors for a limited pool of talent.) Furthermore, a substantial number of engineering grads in the U.S. are foreign nationals who, without a visa or green card, might leave the country – another point Jobs raised in the dinner. He urged Obama to offer automatic visas/green cards to foreign students who earn engineering degrees in the U.S., so that American companies could retain that talent. (Obama replied that immigration reforms like that had to be part of comprehensive legislation – the DREAM Act – which at the time was stalled in Congress.) In short, Jobs’ bold statement – “you can’t find that many [engineers] in America to hire” – was a sweeping generalization, but it reflected a real concern in the tech and manufacturing industries. The U.S. was producing a lot of top-tier engineers, yet there was a mismatch between the skills (and career preferences) of those graduates and the mid-level technical jobs that modern electronics manufacturing demanded.

And what about Jobs’s broader pronouncement that “those jobs aren’t coming back” to America? At least in the near term, this was largely accurate. Even President Obama would later acknowledge that some lost manufacturing jobs simply won’t return. During a 2012 debate, when pressed about Apple’s manufacturing in China, Obama echoed Jobs’s sentiment, saying “there are some jobs that are not going to come back, because they’re low-wage, low-skill jobs.” Indeed, assembly-line positions for devices like iPhones involve repetitive, low-paid work – which, combined with the need for rapid scaling, made them impractical to recreate in the U.S. economy as it stood. High-end manufacturing jobs might be achievable in America, but the era of massive electronics assembly plants in the U.S. was not on the immediate horizon, a reality that both Jobs and, reluctantly, policymakers recognized.

Policy Responses and Legacy of the Exchange

Steve Jobs’s frank commentary had an impact in Washington. President Obama took the warning to heart – that America needed to boost its engineering talent and skilled workforce. According to Isaacson’s biography, Obama was struck by the conversation and repeatedly told his aides in the following weeks: “We’ve got to find ways to train those 30,000 manufacturing engineers that Jobs told us about.” In the wake of the dinner (and as Jobs’s health declined later that year), the Obama administration launched or bolstered several initiatives aimed at U.S. workforce development, STEM education, and even reshoring manufacturing:

• Jobs Council “Engineer” Initiative: President Obama tasked his Council on Jobs and Competitiveness (a panel of business leaders) to develop proposals for increasing the supply of engineers. In fact, a senior official noted that after talking with Jobs about advanced manufacturing, Obama asked his Jobs Council to work on graduating an extra 10,000 engineers a year – a plan that would raise the annual number of engineering graduates to about 130,000. This goal aligned with what industry leaders were saying: the U.S. needed more engineers and tech workers to stay competitive. (Around the same time, in June 2011, Obama also launched the Advanced Manufacturing Partnership, bringing together universities and companies to invest in new manufacturing technologies and worker training.)

• Vocational Training and Community Colleges: The administration put a new emphasis on training programs for the kinds of skilled technicians Jobs spoke about. In early 2012, Obama’s budget proposed an $8 billion Community College to Career Fund to train 2 million workers for fields like high-tech manufacturing. The idea was to encourage partnerships between employers and community colleges to produce graduates with in-demand skills – precisely the kind of practical engineering tech education Jobs advocated (e.g. “Tech schools or trade schools could train them”). Obama publicly stressed the value of vocational education, saying the country must “train workers for the skills that businesses are looking for right now”. This push for STEM and vocational education was reflected in programs like Skills for America’s Future and the expansion of apprenticeships. While funding had to be approved by Congress (and faced political hurdles), the message from the White House was clear: America needs to skill-up its workforce.

• STEM Education and Immigration: Obama also continued to call for strengthening STEM (science, technology, engineering, math) education at earlier levels – for example, initiatives to hire 100,000 new STEM teachers and improve math/science curricula. And though comprehensive immigration reform stalled, the administration (and later, bipartisan groups in Congress) pushed for provisions to staple green cards to advanced STEM degrees so that foreign-born engineers could stay in the U.S. after graduation. This was very much in line with Jobs’s suggestion at the dinner to retain talent educated in America.

• Encouraging “Insourcing” and Manufacturing in the U.S.: In subsequent years, Obama highlighted companies that brought manufacturing back to the States. He proposed tax incentives for “insourcing” jobs and spoke of creating good manufacturing jobs at home – for instance, applauding examples like Ford, Intel, and smaller companies building plants in the U.S. While Apple did not move iPhone assembly back, the administration’s stance put a spotlight on the issue. By 2013, Obama was proposing a network of Manufacturing Innovation Institutes to develop advanced manufacturing capabilities (one such pilot institute was launched for 3-D printing technology). All these efforts were about making high-value manufacturing viable in America – so that even if low-skill assembly jobs “aren’t coming back,” the U.S. could compete in building the more advanced products of the future.

It’s difficult to draw a straight line from the Steve Jobs dinner to specific policies, but contemporaries noted a connection. The conversation “made a strong impression” on Obama. Shortly after Jobs’s death in October 2011, Obama publicly praised Jobs’s vision and discussed how the U.S. needed to “find the next Steve Jobs” and support entrepreneurs and engineers. He even mentioned in an interview that Jobs had given him a personal gift of a new iPad, indicating a warm relationship despite their frank disagreements. And in a tribute statement, Obama acknowledged that Jobs had “bravely” and “boldly” pushed for change.

In sum, Steve Jobs’s warning that Apple’s manufacturing jobs were unlikely to return kick-started an honest dialogue about American competitiveness. Jobs essentially argued that the U.S. had lost its edge in mid-level manufacturing skills – and the onus was on policymakers to catch up. The Obama administration responded by emphasizing training, education, and innovation in manufacturing. While progress was gradual, this exchange helped crystallize the challenges of globalization for the tech industry. It highlighted the need for America to invest in its human capital – so that perhaps, in the long run, some of those jobs (or new high-tech manufacturing jobs) could come back. As Jobs bluntly put it to the President: educate the engineers, and the factories will follow politifact.com. Whether that promise can be realized remains an ongoing policy quest, but the 2011 dinner conversation undeniably put a spotlight on the issue at the highest level of government.

What can and should be Manufactured in the U.S.?

Beyond Tariffs: Non-Tariff Barriers U.S. Companies Face Abroad

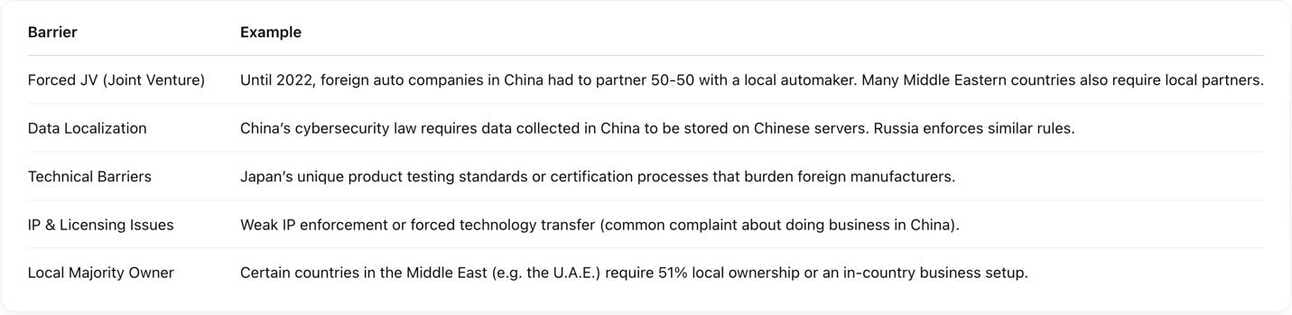

When U.S. companies do try to export or operate in foreign markets, tariffs are only one hurdle. Equally daunting are various non-tariff barriers and restrictive regulations that foreign governments impose. These measures often require U.S. firms to adapt or invest locally (sometimes on unfavorable terms) as the “price” of market entry. Some common global trade restrictions beyond simple import tariffs include:

Unique Standards and Regulations: Countries can use bespoke standards and regulations to impede foreign products. For example, Japan historically employed non-tariff barriers such as unique technical standards, complex certification procedures, and powerful industry associations that control market access. U.S. exporters to Japan have cited obstacles like stringent food and consumer product standards unique to Japan, and a requirement to show prior track record in Japan for certain contracts (making it hard for new entrants). Such “Japan-only” rules mean a U.S. company might have to redesign a product or navigate lengthy approval processes, raising the cost of entry. Similarly, Europe’s regulations (like chemical safety rules under REACH, or data privacy under GDPR) while not aimed specifically at the U.S., can act as barriers if American firms struggle to comply or bear higher compliance costs than local firms.

Joint Venture and Local Partner Mandates: A number of countries mandate that foreign businesses cannot operate independently but must partner with a local firm (often with local majority ownership). Many Middle Eastern countries have had such rules. For instance, until recently, the UAE’s commercial law required any foreign company outside of free zones to have a 51% Emirati partner. Saudi Arabia also historically required foreign investors in many sectors to form joint ventures with Saudi partners. These rules compel U.S. companies to share profits (and often control and technology) with a local entity. They can also pose risks if the chosen local partner’s interests diverge. While some countries are relaxing these requirements as part of liberalization (Saudi Arabia under Vision 2030 has eased foreign ownership limits in certain sectors), forced joint ventures remain in practice in parts of Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. Even India, until the 2010s, required JVs in sectors like insurance (cap on foreign ownership). The intent of such rules is usually to ensure local participation, develop local businesses, or control strategic industries – but the effect for U.S. firms is a barrier to full freedom of operation.

Foreign Ownership Caps and Structure Restrictions (China case): China has long maintained an extensive “Negative List” of industries where foreign investment is restricted or prohibited. In sectors deemed sensitive or important (from telecommunications to media to autos), China either bans foreign firms or limits them to minority stakes. A prominent example was the auto industry – until 2022, China required foreign automakers to form 50-50 joint ventures with Chinese automakers to manufacture in China. Companies like GM, Ford, Toyota, VW all had to partner with local state-owned firms, effectively transferring some know-how. The U.S. Trade Representative has criticized this policy as “forced technology transfer” in exchange for market access. (China did finally remove the JV requirement for autos in 2022, allowing foreign automakers to own Chinese factories fully – Tesla was one of the first to have a wholly foreign-owned car plant there.) In other sectors, China still bars foreign ownership – for instance, Internet content and social media. This is why companies like Facebook and Google are blocked entirely (since 2009 and 2010 respectively)rather than allowed to operate – Chinese law and censorship rules effectively keep them out to protect domestic platforms. Where partial foreign operation is allowed, China often forces a convoluted structure. Many tech firms use a VIE (Variable Interest Entity) structure to get around foreign ownership bans in telecom and media – essentially a legal workaround where the foreign investor doesn’t directly own the operating company (which must be Chinese-owned). This is a fragile arrangement and reflects the lengths companies go to navigate Chinese restrictions. Data localization is another growing barrier: China (and others like Russia) require that data collected in-country be stored on local servers and impose strict controls, which disadvantage foreign cloud and internet companies. Overall, Chinese industrial policy and regulation present a thicket of non-tariff barriers – from licensing delays, antitrust enforcement that favors locals, to informal pressures on Chinese firms to “buy local.” U.S. businesses often say regulatory uncertainty in China is one of the biggest challenges, beyond any formal law.

Local Content Requirements and Procurement Bias: Some countries stipulate that a certain percentage of a product’s components be sourced locally, or give preferences to local suppliers in government procurement. For example, Indonesia and India have imposed local content rules for products like smartphones (requiring a percentage of parts or assembly in-country). These force U.S. exporters either to set up local production or lose access. Government procurement (buying by state agencies) is another arena: countries might not officially ban foreign bids, but they can craft tenders such that only domestic companies qualify. The U.S. has a “Buy American” tilt in some infrastructure spending too, so this cuts both ways. American firms, however, often face an uphill battle selling to foreign governments that informally prefer domestic champions unless trade agreements ensure reciprocal access.

Intellectual Property and Regulatory Barriers: Beyond overt rules, there are more insidious barriers like weak IP protection (allowing local copycats to emerge and undercut the foreign company) or onerous bureaucratic procedures. Japan in the past was noted for its complex distribution system – products often had to go through layers of wholesalers with established relationships, which favored domestic producers. In some markets, cultural and relationship factors (while not formal barriers) mean foreign newcomers struggle to break in – e.g. Japan’s keiretsu corporate networks historically favored business within the group, excluding outsiders. Also, many nations have state-owned enterprises (SOEs) that dominate certain sectors (energy, telecom, banking) and may receive preferential treatment, making competition tough for foreign private firms. China’s SOEs, for instance, benefit from subsidies and implicit government backing, and they often get priority in sectors like finance, telecom, resources – effectively crowding out or disadvantaging foreign competitors.

In summary, U.S. companies often face a host of “beyond-tariff” barriers in global markets: rules compelling them to partner locally, biased standards and licensing, limitations on ownership or operations, and unequal enforcement of laws. While tariffs have come down globally over the last few decades, these non-tariff barriers (NTBs) have gained prominence as tools to protect markets. The 2025 U.S. National Trade Estimate report catalogs hundreds of such foreign barriers, including technical regulations, discriminatory licensing, digital trade restrictions, investment caps, subsidies for local firms, and more. All of these deny U.S. exporters and investors a level playing field or “reciprocal” access to those markets.

For instance, a U.S. medical device company might face low tariffs in Country X, but if Country X only reimburses domestically-made devices under its health system, that’s a de facto barrier. Or a U.S. cloud computing firm might be allowed to sell services in Country Y, but if data must be stored on local servers and a local partner must hold the data center license, the foreign firm is at a disadvantage. These complexities underscore that market access is about more than tariffs – and U.S. trade negotiations increasingly focus on removing such behind-the-border hurdles.

Table 3: Forced Barriers faced by U.S. Corporations on foreign markets

Conclusion: Prioritizing Fair Reciprocity and Protecting U.S. Interests Abroad

The analysis above leads to a clear argument: U.S. trade strategy should focus on achieving fair reciprocity in market access and safeguarding the interests of American companies overseas, rather than fixating solely on tariff levels or trade deficits. Given that the U.S. economy is not highly export-dependent in aggregate, the traditional approach of pushing foreign countries simply to buy more American exports (or matching their tariffs one-for-one) addresses only part of the issue. What U.S. firms need is the ability to compete on equal terms in those foreign markets – whether via exports or by operating there.

“Fair reciprocity” means that if the U.S. keeps its market relatively open (which it does, with generally low tariffs and few explicit barriers), then U.S. companies should get equally open access abroad. In practice, this entails negotiations to dismantle the kinds of non-tariff barriers described: urging partners to remove joint-venture mandates, relax foreign ownership caps, enforce intellectual property rights, eliminate discriminatory standards, and so on. For example, if American banks can only own 50% of a venture in Country A while we allow that country’s banks 100% ownership here, that’s an imbalance to rectify. U.S. policymakers have started to emphasize this. A recent White House fact sheet noted that non-tariff barriers deprive U.S. manufacturers of reciprocal access and called out practices like unfair licensing and data restrictions. Addressing those would go a long way to leveling the playing field.

Moreover, protecting U.S. in-country interests in global markets is vital. This means standing up for U.S. companies against forced tech transfer, theft of trade secrets, or political pressures. It also means ensuring dispute resolution mechanisms are in place – so if an American firm is treated unfairly by a foreign regulator, there’s recourse. Trade agreements and bilateral investment treaties often contain chapters on these issues. For instance, the USMCA (NAFTA’s successor) includes provisions on intellectual property and digital trade that aim to secure fair conditions for U.S. businesses in Canada and Mexico. Future deals, whether with the EU, UK, or Indo-Pacific nations, will likely put reciprocity and non-tariff issues front and center.

Another dimension is that not all “free trade” is fair trade from the U.S. perspective. If Country B imposes 0% tariffs but then slaps a foreign firm with an arbitrary antitrust fine or excludes it from government contracts, that’s not genuinely open trade. Thus, U.S. strategy has shifted toward enforcing trade agreements that include regulatory fairness, labor and environmental standards, and provisions against state subsidies that distort competition. The goal is to create a rules-based environment where U.S. companies (and workers) can compete based on quality and innovation, not face hidden penalties just for being foreign.

At the same time, the U.S. should use its leverage (access to the huge American market) to demand reciprocal treatment. Many countries depend on selling to the U.S. consumer; America can insist that in return, those countries remove barriers to U.S. goods and firms. This doesn’t necessarily mean tit-for-tat identical tariffs (since the U.S. might prefer to keep tariffs low for cheaper imports), but rather equivalent openness. For example, if the U.S. allows a foreign automaker to build factories or acquire companies in the States, we expect that foreign government to allow U.S. automakers the same freedom on their soil. If not, trade tools such as targeted tariffs or investment restrictions could be employed to encourage compliance. The concept of “reciprocal access” is thus about mutual fairness – each side should give the other’s businesses the same opportunities at home that it enjoys abroad.

Finally, focusing on U.S. interests in global markets means recognizing that American prosperity is tied not just to export volumes, but to the success of American companies wherever they operate. If Coca-Cola’s sales in Africa grow or Google gains ad revenue in India, that ultimately benefits the U.S. economy (through profits repatriation, stock value, etc.), even if nothing “exported” shows up in customs data. Therefore, U.S. trade policy must encompass advocating for those overseas business interests. This can involve diplomacy (e.g. pressing China to let U.S. tech firms operate, or pushing allies to adopt our IP standards) and using forums like the WTO to challenge unfair practices.

In conclusion, the U.S. has a unique economic model: huge internal demand, a strong services and innovation sector, and globally deployed companies. It doesn’t rely as heavily on exports for GDP as other nations, but it absolutely needs fair access to world markets for its firms and their foreign-earned revenues. A successful U.S. trade strategy in the 21st century will therefore emphasize enforcing fair rules (beyond tariffs), reducing non-tariff and structural barriers abroad, and ensuring reciprocal openness, so that U.S. exports and companies can compete on equal footing. By doing so, America can protect its long-term economic interests – including manufacturing niches that are viable to reshore – without retreating from global engagement. The aim is a level playing field, where trade is truly mutually beneficial, and where the global operations of U.S. companies are respected and allowed to flourish. This approach acknowledges the realities detailed in this report: the U.S. economy’s strength lies not in export dependency, but in its innovative firms and global reach – assets best defended by demanding fairness and reciprocity in international commerce.

Erasmus Cromwell-Smith

April 29th 2025.

Sources:

Braun, K. (2023). How the 19th century boosted America to the top of the world corn market: A history of U.S. grain trade

(LinkedIn article summarizing U.S. Agricultural History Society findings).

Reuters. “By the numbers: The erosion of US grain export dominance.” April 2, 2025

Obelkevich, J. (2007). Americanisation in British consumer markets, 1950-2000

World Bank – Exports of Goods and Services (% of GDP)

Walmart China – Company facts

P&G Company Profile – Cascade (2023)

Meta Platforms Inc. 2024 Financial Report – Revenue by region

Alphabet Inc. – 2017 Annual Report (via Wikipedia)

Axios – “Steve Jobs to Obama: Those jobs aren’t coming back.” (2011)

Waynesboro Record Herald – Editorial: Steve Jobs and American jobs (2012)

Trade.gov – Japan Trade Barriers (2024)

Labor Notes – Walmart in China (2016)

Stanford FSI Brief – China’s Joint Venture Requirements (2024)

Investopedia – Major U.S. Tech Companies Blocked in China (2021)

U.S. Chamber of Commerce – The Transatlantic Economy 2023, Chapter 2

Executive Order 14257 (Federal Register 2025) – “Depriving U.S. manufacturers of reciprocal access…”

Sources

• Walter Isaacson, Steve Jobs (2011) – see Chapter 41, which recounts Jobs’s meetings with Obama (includes Jobs’s quote “Those jobs aren’t coming back” and discussion of China needing 30,000 engineers vs. U.S. capabilities).

• The New York Times, “Apple, America and the Squeezed Middle Class” (Jan 2012) – investigative report that first publicized the Obama–Jobs dinner exchange and detailed Apple’s overseas operations (e.g. the need for 8,700 engineers to supervise 200,000 workers and China’s 15-day hiring advantage).

• Politifact fact-check on Michele Bachmann’s statement (Nov 2011) – confirms Steve Jobs told Obama that Apple “needed 30,000 engineers” in China and “you can’t find that many in America,” and that Obama was urged to train more engineers as a result.

• SFGate (San Francisco Chronicle), “Steve Jobs bio sheds light on Obama relationship” (Nov 1, 2011) – summary of Isaacson’s account, describing the Feb 2011 dinner and Jobs’s criticisms (lack of U.S. manufacturing engineers, suggestion to offer green cards to foreign engineering grads).

• AppleInsider, “Apple highlights creation of 514,000 jobs in America” (Mar 2012) – notes Obama’s question to Jobs and the “Those jobs aren’t coming back” answer, illustrating the public pressure on Apple.

• Reuters, “Obama calls for focus on vocational training” (Feb 13, 2012) – reporting on Obama’s 2013 budget proposal with $8 billion for community college training to support manufacturing and other industries.

• Politico, “Obama sparred with Steve Jobs over outsourcing” (Jan 21, 2012) – cites the NYT report of the dinner dialogue, quoting Obama’s question “Why can’t that work come home?” and Jobs’s reply “Those jobs aren’t coming back.” Also notes Jobs’s critique that regulations hinder U.S. business.

• Politico, “Obama extols Jobs’s vision” (Oct 5, 2011) – mentions Obama asking his Jobs Council to boost engineering graduates by 10,000 per year (to ~130k) after discussions with Jobs.

• CNNMoney, “Why Apple will never bring manufacturing jobs back to the U.S.” (Oct 17, 2012) – analyzes Apple’s China operations; recounts Jobs’s October 2010 meeting with Obama where he called America’s education an obstacle and noted Apple “needed 30,000 industrial engineers” in China. Also mentions Obama’s debate remark that some jobs won’t come back.

• Dartmouth/Tuck School of Business, “Bringing Macs Back to the U.S.” (Dec 2012) – discusses Apple’s supply chain strategy; opens by recounting Jobs’s Feb 2011 dinner quote and noting Tim Cook’s later decision to assemble some Macs in USA.

• U.S. education stats: National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) data on engineering degrees – showing ~93,000 bachelor’s in engineering in 2010-11; and Computerworld report on Obama’s engineering push, noting 126,000 total engineering graduates in 2009. These figures provide context for Jobs’s statements about the talent pool.